St. Philip Neri blessing the departing seminarians of the English College. Fr. V.J. Matthews tells us that St. Philip would hail the seminarians, whose college is directly across from San Girolamo, with the words Salvete Flores Martyrum, “Hail, flowers of the Martyrs” (Matthews 85). Edited photo by Fr. Lawrence Lew, OP. (Source).

In a recent post, I suggested that Rod Dreher’s The Benedict Option is a flawed, if well-intentioned, strategy for the Church in our times. I stand by that opinion. I also would like to offer my own “option,” as so many others have done. I will refrain from detailing specific suggestions and strategies, as I have neither the time nor the knowledge nor the experience to profitably contribute to any discussion of specifics. Nonetheless, I think I can say a few things about the general spirit and principles of what we might choose instead of The Benedict Option.

For starters, it would be called something different. Although St. Benedict is an eminent and powerful patriarch, I submit to you that, for our purposes, we must look at another man in an era far more like our own, a man whose spiritual sons also offer powerful examples. That man, of course, is St. Philip Neri.

Early Modernity as Proto-Postmodernity

Like Dreher, I choose my patron saint in part because I think the unique conditions of our own moment deeply resonate with those which St. Philip faced. Any comparison between different periods of time are naturally going to fall flat in certain specifics. But consider, if you will, the following phenomena.

The rise of the Internet, like the advent of printing, has opened up new models of knowledge and new conceptions of the self. Our lives are ever more global, even as new forms of nationalism emerge. We are increasingly aware of various forms of religious difference. Some are extremist, and even violent (see, inter alia, the Münster Rebellion and the sects of the Interregnum). Within the Church, we face public in-fighting among the Cardinals, dangerous sacramental, moral, and doctrinal laxism, a German Church that is falling apart, and a Pope whom the Roman People themselves dislike. We face serious problems with the climate. Our educational aspirations and models are increasingly oriented towards social climbing, even as our specialties are becoming narrower. Literary and textual criticism set the terms of debate in the academy. More broadly, sexual mores have changed considerably, and culture war is the order of the day. Homosexuality and gender nonconformity have emerged as increasingly widely-recognized social phenomena. Our civilizational relationship with Islam is complicated, to say the least. Class divisions and structural inequality have led to political instability. Indeed, unthinkable political events, stemming in large part from those class frictions, have jettisoned any sense of certainty we might hope to sustain.

St. Philip arrived in Rome shortly after just such an unthinkable event. In 1527, the armies of the Emperor descended upon the Papal States and launched a horrifyingly brutal sack of the Eternal City. Both Lutheran and—more scandalously—Catholic soldiers raped, pillaged, and desecrated their way through Rome. It was the second and last sack of Rome committed by civilized Christians, and it put an effective end to the Renaissance in that great city.

Alfonso Cardinal Capecelatro, one of St. Philip’s nineteenth century biographers, describes the event as:

…the terrible sack of Rome in 1527, which had no parallel in the history of the Church, whether regarded as a warning or a chastisement. We must go back to Attila and Genseric to find any event which even distantly approaches it in horror; and even those barbarians were civilized and even reverent in comparison with the soldiers of the most Catholic king and emperor, Charles V. A drunken, furious horde of Lutherans and Catholics together was let loose upon Rome…there were…unutterable outrages not to be thought of without a shudder. (Capecelatro 23).

Pertinent to our purposes, however, is the effect that this calamity left on the culture of Rome. Here, too, Capecelatro is a helpful resource.

To enter into the city of the Holy Apostles Peter and Paul at a time when their authority was spurned, vilified, and trampled into the mire by a terrible heresy; to visit the spots hallowed by the blood of martyrs when all around were the hideous traces of their recent profanation; to live in the holy city when the lives of the clergy themselves were dissolute or unbecoming, when paganism in science and letters and art was alone in honours must have been, to the heart of a saint such as Philip’s, an anguish inconceivably bitter. (Capecelatro 24).

A blasphemous mock-Papal procession during the 1527 Sack of Rome. (Source).

If, like Dreher, we wish to compare our own times to the sack of Rome, we ought to look a thousand years later than he does. As with Rome circa 1535, we live in a culture riddled with “a terrible heresy,” Dreher’s “Moralistic Therapeutic Deism” (among others). We Christians in America have witnessed the martyrdoms of our Coptic and Middle Eastern brethren over mass media. The Church is still reeling from a time when “the lives of the clergy themselves were dissolute [and] unbecoming.” The sins of clerical sex abuse continue. And insofar as there is a pagan tendency in our culture today (Camille Paglia certainly thinks there is), it resides in our “science and letters and art.”

While I don’t wish to belabor the point too much, I’ll add that not all is cause for alarm. Many of the good things about early modernity are also true today.

In 1850, Fr. Faber gave a series of lectures to his spiritual sons at the London Oratory. His subject was “The Spirit and Genius of St. Philip Neri.” The second lecture includes a long consideration of St. Philip as the “representative saint of modern times” (Faber 38). Faber argues,

The very essence of heresy and schism is constantly found in the disobedient and antiquarian worship of some pet past ages of the Church, in contradistinction to the present age, in which a man’s duties lie, and wherein the spirit and vigour of the living Church are in active and majestic energy. The Church of a heretic or schismatic is in books and on paper…A Catholic, on the contrary, belongs to the divine, living, acting, speaking, controlling Church, and recognizes nothing in past ages beyond and edifying and instructive record of a dispensation, very beautiful and fit for its day, but under which God has not cast his lot, and which, therefore, he has no business to meddle with or to endeavour to recall. One age may evoke his sympathies, or harmonize with his taste, more than another. Yet he sees beauty in all and fitness in all, because his faith discerns Providence in all. (Faber 40-41).

Dreher would do well to note Fr. Faber’s point. The uncharitable pessimism that animates so much of The Benedict Option is not entirely misbegotten, but certainly falls short of the truth. And why? In part, because Dreher never mentions Church history. His historical narrative of Christianity in Western culture overlooks the actual ways that Christians have responded to modernity since the 16th century. Fr. Faber does not. Instead, he writes,

…it is plain that we are in possession of a great many more doctrinal definitions than we were; the limits of theological certainty are immensely extended. Just as verified observations have extended the domain of the physical sciences, so the number of truths which a believer cannot, without impiety, or in some cases formal heresy, reject, has added to the domain of theology…Now this greater body of certain dogmatic teaching must necessarily influence the whole multitude of believers. It it tells upon literature; it tells upon popular devotion; it tells upon practice…and lastly, it tells upon ecclesiastical art…Neither, in speaking of Modern Times, must we omit to notice the natural connection there is between an increased knowledge of dogma, and the spirit of reverent familiarity in devotion, which has been so prominent a feature in the later Saints. The more extended the vision of faith becomes, th more familiar a man necessarily grows with the sacred objects of which that faith so infallibly assures him…We must not omit then to name the increase and greater universality of mental prayer, the more generally adopted systematic methods of self-examination, the more common practice of spiritual reading, the ways of hearing mass, the obligation of meditation made the condition in most cases of gaining the indulgences of the Rosary, and other things which are all so many marks of what is called nowadays the increased “subjectivity” of the Modern Mind.(Faber 44-46, 49-50).

Fr. Frederick William Faber, founder of the Brompton Oratory in London. (Source)

Faber adds that anyone who would ignore this latter tendency towards “subjectivity” when seeking to evangelize would inevitably “find himself miserably out in his reckoning…The experiment would correct itself” (Faber 50). While Fr. Faber’s optimism is perhaps just as simplistic as Dreher’s pessimism, his perspective helps us attain the proper, prudential, balanced orientation towards modernity that The Benedict Option flatly misses.

Faber offers his historical assessment as a prelude to the consideration of St. Philip Neri’s life and spirituality. For Fr. Faber, St. Philip combines in his person and example the very best of what modernity has to offer. After all, Faber notes, Pippo Buono was ordained while the Council of Trent met. His movement began in an urban setting, “the very capital of Christendom itself,” and he managed to meet and influence “people of all nations” (Faber 51).

Even St. Philip’s personality was that of

…a modern gentleman, of scrupulous courtesy, sportive gaiety, acquainted with what was going on in the world, taking a real interest in it, giving and getting information, very neatly dressed, with a shrewd common sense always alive about him, in a modern room with modern furniture, plain, it is true, but with no marks of poverty about it; in a word, with all the ease, the gracefulness, the polish, of a modern gentleman of good birth, considerable accomplishments, and very various information. (Faber 52).

Fair enough. But why bother applying the example of this modern saint to our peculiar cultural and religious circumstances? It is one thing to say that a saint might have something to teach us. It is another thing altogether to say that a saint’s teaching might prepare us for the peculiarly harsh cultural conditions which seem to loom on the horizon (Dreher wasn’t wrong about all of it).

Faber answers this question, too. He writes of St. Philip:

He came to Rome at one of the most solemn crises of the Church; the capital was full of Saints, and full of corruption too. He was the quietest man at his hard work that ever was seen; yet he magnetized the whole city; and when he died he left it quite a different city from what it was, nay, with the impress of his spirit and genius so deep upon it, that it was called his city, and he the apostle of it, second only to St. Peter. It was no man clothed in camel’s hair, with the attractive paraphernalia of supernatural austerities upon him, no St. Francis, with his Chapter of Mats all round the Porziuncula, that the city and its foreign visitants went so anxiously to see; it was simply an agreeable gentleman, in a comfortable little room, apparently doing and saying just what any one else might do or say as well. He had come at his right time; he suited his age; men were attracted; he fulfilled his mission. (Faber 53).

St. Philip’s example is pertinent to our present debate insofar as he reformed late Renaissance Rome, a society much like ours, by means far more achievable and far more charitable than the contorted stratagems of The Benedict Option.

“Roots Are Very Important”

Admittedly, those words weren’t spoken by St. Philip. They’re actually the climactic revelation from Paolo Sorrentino’s La Grande Bellezza (2013), one of my favorite films—a story that takes place in Rome. And as with all things Roman, St. Philip is never far away.

Two very singular facts stand out about St. Philip. One is that he was deeply attached to the Eternal City. And, relatedly, he never wished to start a religious order. He always claimed that the Congregation was entirely the work of Mary and the Holy Spirit. St. Philip was even reluctant to permit some of his sons to begin a house in Naples, a decision which would ultimately yield the harvest of many saints. Long before that, St. Philip required those priests he sent to San Giovanni dei Fiorentini to return to San Girolamo every day for the exercises of the Oratory—even in sweltering heat and downpours of rain.

Borromini’s facade of the Roman Oratory, sketched 1720’s. (Source).

In my recent post on St. Philip’s Benedictine tendencies, I noted that St. Philip understood that spiritual fatherhood can only be built upon a certain degree of stability. Along with that comes a strong sense of place, an immersion in the particular life of any given community. This decentralized localism is why every house of the Oratory throughout the world has its own unique spirit and apostolate. The Congregation only unites under the general aegis of St. Philip’s inspiration, not the ordinary vows of a religious order. To use a somewhat hackneyed analogy—if the Jesuits are the global corporations of the ecclesiastical world, then Oratorians are the folks who run mom & pop shops. However, there is a deeper meaning to this organizational quirk that we will have occasion to examine soon.

That domestic spirit can be summed up by the Oratorian conception of nido, or “nest.” As one source has it,

St Philip’s disciples and penitents sometimes sought him out in his room, where the Exercises of the Oratory were held in the early days. The Oratorian does not emulate a monastic detachment which would periodically surrender one’s very bedroom in manifestation of the premise that material goods are merely ad usum. The Oratorian identifies his room as a nido, a “nest.”

Strong Christian community requires roots. Dreher, as well as the good folks over at places like Front Porch Republic and Solidarity Hall, has frequently made this point over the last several years. It is not a new idea. The Benedict Option is peppered with quotes from Wendell Berry, the godfather of all American localist movements today. If Dreher’s Christian communitarianism is to succeed, then it must be predicated on something very much like the Oratorian sense of place. We would be wise to draw upon the domestic spirit of St. Philip’s nido.

The effigy of St. Philip Neri, created from life once he could no longer lead the pilgrimage to the Seven Churches. Currently in possession of the Roman Oratory. (Source).

And that very sense of local domesticity often leads to precisely the kind of worldly engagement that Dreher’s book tends to overlook and minimize. Although St. Philip was by no means a polemicist, he took an active interest in the affairs of the world—as they transpired within the walls of Rome. He intervened in affairs of state only once, when he required Baronius to withhold absolution from the Pope until the latter had reversed the excommunication of Henri IV. This successful bit of string-pulling on St. Philip’s part probably kept the French crown Catholic for the duration of the Bourbon dynasty.

Of course, there is more to Oratorian domesticity than that. St. Philip’s genius lies not only in his stability, but in the way he invested so much of his spiritual ministry with romanità (in every sense of the word). He drew his principle practices from the sun-baked stones and the boiling air of the Eternal City, as if by some secret alchemy. He was famous for leading ever-more popular pilgrimages along the path of the Seven Churches. And all this, to compete with and vitiate the heathen delights of the Carnival. Where else but in Rome could a saint freely lead and care for such masses of pilgrims along such a venerable route? Where else in the history of modern Europe do we see such a providential alignment of personality, place, and practice against the pagans? The established traditions of spirituality which had already formed Rome were in turn re-formed by St. Philip. It is for this reason that he has been given the honorific title of “Apostle of Rome,” alongside Saints Peter and Paul.

As long as Christianity remains tied to the parish structure, it will always be a local religion. Consequently, St. Philip Neri’s unique resourcefulness will always be relevant. Especially today. As one writer puts it, “The mission of an Oratorian is to work at ‘home’; the Oratory is thus an apt instrument of the New Evangelization, re-proposing the gospel in formerly Christian societies.” God furnishes us with opportunities all around, if only we wish to see with “the eyes of the dove” (Cant. 1:15 paraphrased).

Illumine the Intellect

Such sight will be clearer and more invigorating if sharpened by the intellect. St. Philip’s exercises in the Oratory constituted a kind of holy pedagogy for the men of Rome. In his biography of the saint, the French Oratorian Louis Bouyer describes it well:

The programme of their meetings took some ten years to crystallize into the following form: reading with commentary, the commentary taking the form of a conversation, followed by an exhortation by some other speaker. This would be followed in turn by a talk on Church History, with finally, another reading with a commentary, this time from the life of a saint. All this was interspersed with short prayers, hymns and music, and the service always finished with the singing of a new motet or anthem. It was taken for granted that everyone could come and go as they chose, as Philip himself did. He and the other speakers used to sit quite informally on a slightly raised bench facing the gathering. (Bouyer 54).

Another author gives us a more detailed understanding of the kinds of materials that St. Philip and his sons were reading, hearing, and discussing in the exercises:

In St Philip’s time, the most important of his Exercises, which came to be known as the Secular Oratory, or in some places the Little Oratory, was a daily practice spread out over two to three hours during the leisurely Roman siesta and consisting of (1) a period of mental prayer; (2) a reading from the Scriptures or some spiritual book (e.g., Denys the Carthusian, John Climacus, Cassian, Richard of St Victor, Gerson, Catherine of Siena, Innocent III’s De Contemptu Mundi, Serafino da Fermo’s Pharetra Divini Amoris—St Philip’s favourite readings were the Laudi of Jacopone da Todi and The Life of Blessed Colombini by Feo Belcari), followed by a “discourse on the book,” a commentary and dialogue on the subject of the reading; (3) a discourse on the life of a saint; (4) a moral exhortation—a discourse on the virtues and vices; (5) a discourse on the history of the Church; and finally (6) an oratorio or spiritual canticle. (Source).

Herein we find the germ of Oratorian life, “the daily use of the Word of God” (Talpa, quoted here). St. Philip’s model is eminently conversational. The Oratory converts and sanctifies, not only through its stated arms of the sacraments, prayer, and preaching, but through discussion—and, as well shall see, aesthetics.

St. Philip was not, however, given to ostentatious and idle chatter. He well understood the words of St. James, that “the tongue is a fire, a world of iniquity” (James 3:6 KJV). Consequently, he always urged his sons to mortify their speech as well as their reason and intellect. The Oratorians were to be wise, intelligent, even scholarly. But they were not to speak freely of the arts and sciences, nor were they to flaunt their learning. One Oratorian father went so far as to feign ignorance of Latin; another would always try to change the subject when any scholarly or humanistic matter came up in conversation. Amare nesciri—“to love to be unknown”—these words were ever on St. Philip’s lips.

The Venerable Cardinal Caesar Baronius, author of the Annales Ecclesiastici, father of Church history. (Source).

None of this is to suggest that St. Philip was actively anti-intellectual. Far from it! After all, St. Philip was a devoted student of theology and philosophy in his younger days, and Father Faber calls even the mature St. Philip a “great student of history” (Faber 53). Those words could perhaps be more truly applied to St. Philip’s spiritual son, the Venerable Cardinal Caesar Baronius. It was St. Philip who commanded Baronius to write the Annales Ecclesiastici, the first great work of church history in modern times. The project served a few functions. First, it got Baronius off of preaching, as he had the unpleasant but slightly amusing habit of turning every sermon into a lengthy and vivid discourse on the everlasting torments of hell (I hope that, when he is eventually canonized, the good Cardinal becomes the patron saint of horror writers). The project also productively occupied Baronius’s prodigious intellect, which St. Philip mortified in many other ways. For instance, Baronius was given kitchen duty so frequently that St. Philip playfully wrote above the stove, “Baronius, Coquus Perpetuus.” Finally, St. Philip and Baronius conceived of the book, which unexpectedly became a decades-long enterprise, as a way of challenging the then-dominant historiography of Protestant authors, as exemplified by the Magdeburg Centuries. A cynic might call this bias. In context, it’s perhaps more fair to interpret Baronius’s motive as one very much akin to those that animate the scholarly disputes of our own day. And because of Baronius’s thoroughgoing method, academic rigor, and meticulous attention to detail, the Annales were received with respect even by those who disputed its claims. It was so impressive a work that several centuries later, Lord Acton could honestly call it “the greatest history of the Church ever written” (Source).

St. Philip urging Baronius to write the Annales. (Source).

Nor was Baronius the only model of learning in the Oratory. His fellow cardinal, the aristocratic Francesco Maria Tarugi, was the fox to his hedgehog. Louis Bouyer writes that Tarugi “captivated everyone with his natural eloquence and was never at a loss, no matter what the topic of the moment might be” (Bouyer 64). Here again we see the mark of what we may call the specifically Oratorian genius—erudition crowned with beautiful style and fluency in speech.

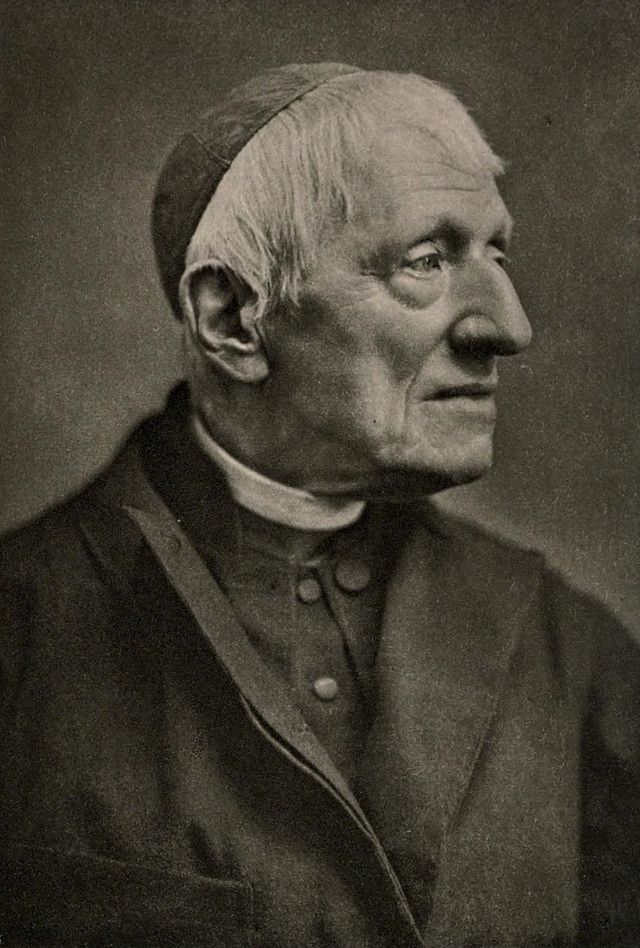

If St. Philip stands for an appropriate humility of the intellect, Baronius for a rigorous love of truth, and Tarugi for eloquence in discourse, then we must turn to a fourth figure, the greatest scholar ever to enter the Oratorian life. I speak, of course, of John Henry Cardinal Newman.

In Newman’s long, productive, and complicated life, a few key themes emerge. Three are worth examining in connection with the intellectual tradition of the Oratory. First, we may duly note that Newman always exhibited a great love of knowledge for its own sake, and thus of Truth as such. As he writes in The Idea of a University,

Useful Knowledge then, I grant, has done its work; and Liberal Knowledge as certainly has not done its work,—that is, supposing, as the objectors assume, its direct end, like Religious Knowledge, is to make men better; but this I will not for an instant allow, and, unless I allow it, those objectors have said nothing to the purpose. I admit, rather I maintain, what they have been urging, for I consider Knowledge to have its end in itself. For all its friends, or its enemies, may say, I insist upon it, that it is as real a mistake to burden it with virtue or religion as with the mechanical arts. Its direct business is not to steel the soul against temptation or to console it in affliction, any more than to set the loom in motion, or to direct the steam carriage; be it ever so much the means or the condition of both material and moral advancement, still, taken by and in itself, it as little mends our hearts as it improves our temporal circumstances. And if its eulogists claim for it such a power, they commit the very same kind of encroachment on a province not their own as the political economist who should maintain that his science educated him for casuistry or diplomacy. Knowledge is one thing, virtue is another; good sense is not conscience, refinement is not humility, nor is largeness and justness of view faith. Philosophy, however enlightened, however profound, gives no command over the passions, no influential motives, no vivifying principles. Liberal Education makes not the Christian, not the Catholic, but the gentleman. (The Idea of a University 120-21).

Newman never abandoned the life of the mind. (Source).

Along with this purity of vision, we naturally find in Newman a perennial appreciation of academic engagement, and when necessary, controversy. Indeed, Newman rose to fame and eventually converted because of his involvement in the ecclesiastical turmoil of the 1830’s and 40’s. He produced his first two great works, Tracts for the Times (1833-1841, in collaboration with others) and The Arians of the Fourth Century (1833) in light of those disputes. Likewise, Newman articulated his great theories of doctrinal development (Essay on the Development of Doctrine, 1845) and the important role of the laity (“On Consulting the Faithful,” 1859) in texts occasioned by ongoing controversies within the Anglican and Roman Catholic churches respectively. And although he could be terribly sensitive to even the slightest criticism, Newman took pains to respond with courtesy, as he did to Charles Kingsley in his famous Apologia Pro Vita Sua (1865). While Newman never sought out polemics and controversies, he was willing to engage in them when the Truth and Honor of God was at stake.

Finally, we ought to remember that Newman was always animated by a sincere love of that singular matrix of the intellectual life—academic community. His experience at Oxford profoundly shaped his worldview. He is, of course, still widely regarded as one of the great theorists of higher learning. The Idea of a University (1852, 1858) remains one of the most influential texts on Catholic education in modern times. But the impression that Oxford left on Newman is deeper and more subtle. Newman was drawn to the Oratory in part because he recognized in it the same collegiality that defined the best of the houses at Oxford. Newman writes,

Now I will say in a word what is the nearest approximation in fact to an Oratorian Congregation that I know, and that is, one of the Colleges in the Anglican Universities. Take such a College…change the religion from Protestant to Catholic, and give the Head and Fellows missionary and pastoral work, and you have a Congregation of St Philip before your eyes. (Newman, quoted here).

Newman first considered the Oratory in part because he hoped to offer a ministry to the intellectuals of Britain:

The local bishop, Nicholas Wiseman, invited them to the former seminary at Old Oscott while they decided what to do. Newman named it “Maryvale” and planned some sort of Catholic educational institute there. But then Wiseman sent them off to Rome for ordination. While there, they examined various religious congregations, and realised that St Philip’s Oratory was the most suitable. The Birmingham Oratory was accordingly set up in Maryvale (2 February 1847), before settling on its present site, with another Oratory in London. (Oxford Oratory).

Sadly, Newman was unable to achieve his dream of an Oratory in Oxford during his lifetime. Fr. Jerome Bertram CO has a monograph on the subject, worth looking into. Suffice it to say, Newman looked upon the university as a major and potentially ripe field for an intellectual, aesthetically sensitive Catholic missionary presence. There is a reason why Catholic ministries to university students are very often called Newman Centers.

The Oratorian tradition of scholarship continues today, as with, inter alia, the work of Fr. Jonathan Robinson of the Toronto Oratory. Here is the cover of his 2015 book, In No Strange Land: The Embodied Mysticism of Saint Philip Neri. (Source).

Insofar as we are trying to draw out principles that might be of use to the Church in the face of the various cultural challenges which prompted Dreher to write The Benedict Option, I think the Oratorian example, particularly as reflected in Newman’s life and work, may be of use. What lesson we should take? That we ought not abandon the universities and all that they stand for. Yes, there are failures of free speech, episodes of intimidation, and other serious problems at many institutions of higher learning. Dreher, to his credit, has done a good job reporting on the recent madness at Middlebury and Evergreen State.

But the universities overwhelmingly remain the central locations of serious intellectual exchange in this country and the world. While there are some impressive institutions of higher learning outside of or parallel to the formal university system, these are few and far between (see, inter alia, the Maryvale Institute and the Institute for Advanced Studies in Culture). For what it’s worth, Alasdair MacIntyre has explicitly argued for a retrenchment of our position within the academy, both in Three Rival Versions of Moral Enquiry (1990) and elsewhere. As Rowan Williams notes in his review of the book, Dreher seems to write off public discourse entirely. Dreher’s decision to do so is very foolish, more likely to hurt than help the position of Christians in our culture. Moreover, it is alien to the quintessentially Oratorian spirit of a man like Newman.

Contemplate Beauty

One of the marks of the Oratorian charism is a devoted attention to aesthetics. Perhaps it is only appropriate that a vocation emerging from and responding to the Neo-Platonist Renaissance should share its love of beauty. The Florentine St. Philip seems to have known instinctively that beauty evangelizes well and widely.

Baroque apse of Santa Maria in Vallicella, by Pietro da Cortona (Source).

The exercises of the Oratory were never complete without a great deal of music. Louis Bouyer tells us that St. Philip “liked the conversations to be interspersed with music and the meetings to be brought to a close by some singing, so that the evening was filled with harmony” (Bouyer 54). St. Philip engaged the talents of some of the greatest Roman composers of his day. Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina took St. Philip as his confessor, and Giovanni Animuccia was so frequently involved that Bouyer tells us, “In all truth nothing but one of Animuccia’s lovely motets could distill the essence of the Oratory and pass it on undiluted” (Bouyer 55). That same essence continued in the Congregation even after St. Philip’s death. Emilio de’ Cavalieri’s Rappresentatione di Anima et di Corpo premiered at the house of the Roman Oratorians in 1600, and as a result, is generally considered the first oratorio.

St. Philip did not limit his careful deployment of beautiful and holy music to the formal exercises of the Oratory. He also knew that the long walks and pilgrimages he conducted around Rome would more easily win souls if they were elevated by sweet harmony. As Bouyer reports,

On such occasions music played a more important role than ever. Animuccia would bring along Rome’s best musicians, and the ‘Adoremus te Christe’ by Orlando de Lassus, or the ‘O vos omnes’ by Vittoria, would mingle with the sound of the fountains’ silvery cascades, of the leaves rustling in the sea breeze…On their way in the freshness of those early summer mornings on the Roman Campagna, Serafino Razzi’s Laudi would alternate with Gregorian Litanies.

At San Sebastiano…would follow a fine Polyphonic Mass, perhaps Palestrina’s wonderful ‘Mass of Pope Marcellus’ or his ‘Ecce Sacerdos magnus’…On their return to the centre of the city they would visit Santa Maria Maggiore on the heights of the Esquiline. Beneath the ceiling which Alexander VI had just decorated with the first American gold to be brought by Christopher Columbus from Peru, and among the Ionic columns of pure white marble, the day would draw to a close in an outburst of Palestrina music, and a ‘Salve Regina’ would fill the falling night with its loveliness gathered from the rivers and the stars. (Bouyer 57-60).

Nor was St. Philip insensible to the appeal of visual beauty. He was fond of Federico Barocci. We can detect in Barocci’s work a certain light sfumato, an airy other-worldliness that hovers over the strikingly intimate scenes the artist depicts. In the works of Barocci, there is something of the spirit of St. Philip, in whom the presence of God was so manifest and so exemplary in one so strangely human.

Madonna di San Simone, by Federico Barocci, c. 1567. (Source).

Some years after St. Philip’s death, the Oratorian fathers commissioned Caravaggio to create a sizeable painting for a side-altar. The result was the famous “Entombment of Christ“ (1603-04), now hanging in the Vatican Museums.

The Entombment of Christ, Caravaggio, c. 1603-04. (Source).

These artistic traditions have not fallen away in later houses of the Congregation. The Brompton Oratory in London is renowned for its architecture as well as its world-class Schola Cantorum. Its founder, Fr. Faber, gained wide respect as a hymnodist and poet. Newman also wrote some excellent verse, though he is more commonly regarded as a master prose stylist; Joyce considered him the greatest prose writer in the English language. St. Philip wrote some poetry too, though he destroyed most of his verses before he died. All that survive are a few religious sonnets. As one Italian author puts it,

Philip was perhaps the first who, after the reform in our poetry effected by Bembo and other distinguished men, treated religion with that fine poetic taste with which Petrarch treated the philosophy of Plato. Philip flourished as a poet about 1540; and then he forsook literature and gave himself wholly to God, and flourished far more in holiness, until his death. But though he no longer wrote poetry, he did not set it altogether aside. He well knew its great uses when guided by a christian spirit, and therefore he made a great point of it in his Congregation. He read poetry himself, and ordered that it should be always read and used by his followers in the way described in our previous notes. (Crescimbeni, quoted by Capecelatro, here).

St. Philip frequently found ways of incorporating the Laudi of Jacopone da Todi into the spiritual reading that formed such an important part of the exercises of the Oratory. It was one of only two books we know he brought with him from Florence. The Laudi was a text to which St. Philip returned frequently throughout his life, and one that always bore new graces (Bouyer 53).

“L’Angelo mostra a San Filippo Neri un dipinto della Vergine con Bambino e San Giovannino,” Circle of Carlo Maratti (Source).

All of this goes to say that St. Philip and his sons were no philistines. They appreciated and, in some cases, produced fine art across a variety of disciplines. While their vocation was never primarily or deliberately aesthetic, Oratorians throughout history have understood the spiritual importance of beauty.

Dreher hits this point pretty well in The Benedict Option. In that sense, my dissent from his recommendation may be more a matter of emphasis than of substance. Insofar as we differ at all, I think my issue is summed up well by Rebecca Bratten Wise:

Perhaps the critics who are timid about these powerful Catholic writers working right now in our midst are waiting for someone else to “baptize” them? Perhaps they are waiting for someone else to say “I heard God there” – because they, themselves, have not learned to open the inner chambers of the ear? Because we do not have a robust Catholic arts culture that teaches us to open all the portals for reception, but instead have embraced a misnamed “Benedict Option” which is all about putting up walls and barriers, drawing those lines in the sand.

Nevertheless, I do strongly criticize Dreher for lacking a sufficiently sacramental vision. The Oratorian aesthetic makes up for this failure, in that it is primarily liturgical.

Live and Love Eucharistically

And thus, we finally turn to the most important feature of St. Philip’s life and charism, the feature which made him a saint and a father of saints—his burning, Eucharistic charity. We can find evidence of St. Philip’s Eucharistic life in the peculiar and highly somatic form of mysticism that we encounter in his vitae. St. Philip never trusted ecstasies and visions, though he was granted such graces himself—usually in connection with the celebration of the Holy Sacrifice.

Capecelatro depicts the scene for us:

But now, in his 76th year, he could no longer restrain the impetuosity of Divine love which glowed within his heart, and he resolved to say Mass in private that he might give free course to his devotion.

“Madonna con Bambino in trono e san Filippo Neri,” Giacomo Zoboli (Source)

From that time his usual method of saying Mass was this: up to the Domine, non sum dignus, everything went on as before; but at the solemn moment which precedes the priest’s communion, those who were in the chapel withdrew, the server lighted a lamp, put out the altar candles, closed the shutters of the windows, locked both doors, and left the Saint alone with God. Philip would have none to witness the raptures of his love, or to check the freedom of his sighs, words, and tears. A notice was then hung on the door, with these words: “Silence—the Father is saying Mass.” He would remain alone with Jesus in the Adorable Sacrament for two hours, hours of contemplation and of prayer with many tears, and urgent intercession for the Holy Church, the Bride of Jesus Christ, that He would render it as holy in the life of its children as it is in its faith and teaching. After two hours the server came back and knocked gently at the door; if the Saint answered, he opened the door, relighted the candles on the altar, opened the window-shutters, and Philip finished his Mass in the usual way. If the server received no answer, he went away for some time longer, nor did he enter the chapel until the Saint gave some sign that he might do so. What passed in those hours is known to God alone; those who saw Philip when his Mass was over were struck with amazement and awe, until his countenance was pale and wasted, as of one about to die. (Capecelatro 131-32).

And this in the immediate age of Trent! What are we to make of these irregularities?

St. Philip’s Mass is not a model of liturgical praxis, but of liturgical spirituality. In his own highly idiosyncratic prayer, St. Philip becomes a universal model of the soul in adoration of the Eucharistic God. St. Philip was, indeed, one of the great apostles of adoration in his time, as he popularized the Forty Hours’ devotion in Rome. Today, the Quarant’Ore remains a tradition of the Church and the Oratory throughout the world.

The Forty Hours’ Devotion at the London Oratory. (Source).

St. Philip’s sons are known for their tender devotion to the liturgical rubrics. In fact, I draw my title from a line in Fr. Jonathan Robinson’s foreword to Resurgent in the Midst of Crisis: Sacred Liturgy, the Traditional Latin Mass, and Renewal in the Church (2014), by Dr. Peter Kwasniewski. Fr. Robinson speaks of an “Oratorian option” not in relation to the early stages of the Benedict Option controversy, but as “a Reform-of-the-Reform ars celebrandi” (Robinson, in Kwasniewski 3). Indeed, the Oratories of the Anglophone world have a particularly strong reputation for their reverent and careful celebration of the Holy Sacrifice of the Mass. As with the best monasteries, the best Oratories exhibit “dignity and magnificence of the liturgical ars celebrandi” (source). In London, Birmingham, Oxford, Toronto, Vienna, Cincinnati, Pittsburgh, Washington, Brisbane, York, Manchester—in short, wherever the spirit of St. Philip prevails over all rivals and distractions—we find a true Domus Orationis, a “House of Prayer” (Matt. 21:13).

The chief fruit of this discipline is supernatural charity. St. Philip sought to found his congregation on this virtue, not the vows which have historically defined the religious state. There is a Trinitarian logic to this plan. For, just as the superabundant love in the heart of the Trinity impels the Three Divine Persons freely to create, redeem, and sanctify, so too should the love of the Oratory overflow into the streets and lead its members to good works. The love of God descends to a love of brethren, which descends in turn to a love of neighbor. Each of these lesser loves ought to confirm, extend, and refine the higher loves. This chain of charity, then, is a veritable Jacob’s ladder, for those in the angelic state are called ever to climb up and down until their passage into beatitude.

Of course, the basic pattern here is not unique to the Oratory. What sets the Oratory apart is its love of the world. A kind of holy worldliness distinguishes the Oratorian spirit, even as St. Philip’s own outlandish behavior earned him a reputation for other-worldliness. I don’t mean to suggest that St. Philip and his sons were given over to the permissive and pagan times in which they lived. Rather, I mean that St. Philip and the Oratorians are characterized by two separate but related qualities that proceed from their Eucharistic life.

First, St. Philip was renowned for prudence. After all, he was a much sought-after confessor. The irony at the heart of so many of his jokes is that, by mocking his own and others’ pretensions, he demonstrated how utterly divorced so many of our lives are from good Christian common sense. In this respect, he was a true fool for Christ very much after the Eastern model. St. Philip’s prudence did indeed appear foolish to those whose vision could not penetrate to the mysteries of God.

From Guido Reni. It seems only appropriate that St. Philip should be so frequently depicted fully vested for Mass. (Source).

While in other ages, prudence led some saints to undertake and advise great hardships for the kingdom, that same virtue taught St. Philip a different path. He drew his own strength from fastidious and hidden rigors, but he always counseled his penitents to avoid excessive asceticism. Once, when the future Cardinal Tarugi, still young and wealthy and vain, came to him for confession, he asked St. Philip if he might wear a hairshirt. St. Philip saw through the man’s pride. He assented—but only allowed Tarugi to wear the hairshirt on top of all his other garments! For such an admirer of Savonarola, St. Philip could hardly have been farther from his practice when it came to matters of mortification. What little he did urge he usually salted with his own brand of humor. He famously took the Dominican novices of the Minerva out on long picnics and urged them to eat and grow fat. So, too, his pleasant indulgence of children was legendary. And what of those long walks with the crowds under the Roman sky?

St. Philip loved the world. He hated its lies and vices, but he was ever able to peer beyond that sordid stratum and into God’s glory. As one source puts it, “St. Philip was the Apostle of Rome, who by means of the ‘counter-fascination of purity and truth’ reconverted both clerics and laymen in the city at the centre of the Church.” Or, as Louis Bouyer tells us,

Does not Philip, in fact, merely yield to Renaissance optimism? Does he not ignore original sin when he bases his apostolate on freedom and confidence? His ‘religion without tears’ surely expects from undisciplined nature what the discipline of grace alone can produce?

…There is no doubt that it was dangerous to go out against the new paganism with no other arms save love, and just as dangerous to expose his apparently vulnerable simplicity to its disturbing influence, yet his outrageous method made him the victorious apostle of neo-pagan Rome. (Bouyer 28-29).

The love that conquered Rome was the fruit of St. Philip’s sacramental interior life. The unique grace of his special relationship with the Holy Spirit was a cardinal element of that life, but so was his ardent devotion to the Eucharist.

It was this element that I found so disturbingly absent in Dreher’s book. There is no properly Christ-like love of the lost in The Benedict Option, only one angry jeremiad after another. And why? Perhaps because Dreher hardly ever mentions the Eucharist. Dreher writes as if Christ’s presence on earth is an afterthought, one tool among many to be deployed in the quest for community. The result is a spiritually crabbed book, insufficiently sacramental and brimming with self-righteous anxiety.

St. Philip shows us another way.

Conclusion

At the end of the day, there is no silver bullet to halt the various troubles that the Church faces in what seems like an increasingly hostile, secular West. Christ never abandons us to the narrow limits of our own imagination and resources. Instead, He furnishes the Church with untold gifts, charisms, and holy exemplars among the saints. In this sense, the recent proliferation of “Options”—to which this essay contributes—is probably a blessing.

But we musn’t forget one ineradicable fact. Christ never raises these lesser creations over His own Body, Blood, Soul, and Divinity. There is no blessing, no vocation, and no grace that can go beyond the work of the Adorable Sacrament. If we forsake the one rock of the Altar and instead build upon the sand of the innumerable personal graces and unique charisms spread throughout the Church Universal, then all of our works will shatter beneath the hammer of the storm.

St. Philip Neri understood this truth and lived it out across the long span of his ministry. Those qualities which distinguish the Oratorian charism—domesticity, localism, intellectual rigor, humility, collegiality, aesthetics, urbanity, prudence, and love of the world—can only be integrated and understood in the light of the sanctuary lamp. St. Philip’s entire life was a ceaseless testament to the power of the Eucharist “for the life of the world” (John 6:52 KJV). In keeping close to the Sacrament and to the example of St. Philip, we may just make it after all.